Denali (Mount McKinley), located in Denali National Park and Preserve is the tallest mountain in North America. Located in south-central Alaska, the mountain's peak is 20,310 feet. Its base-to-peak rise is the largest of any mountain situated entirely above sea level. In August 2015, with President Barack Obama's approval, the U.S. Department of the Interior officially renamed the mountain Denali. Five large glaciers (Peters, Muldrow, Traleika, Ruth and Kahiltna) flow off the slopes of the mountain. The Kahiltna, with a length of 44 miles, is the longest glacier in the Alaska Range.

©Rich Beckman

Moose are the largest members of the deer family, weighing between 800 and 1,500 pounds. In Denali Park, about 2,000 moose roam on the north side of the Alaska Range. Only the males have antlers, which can measure up to six feet from end to end. They prefer to browse on tall grasses and shrubs or in lakes, rivers or wetlands, feeding on aquatic plants at and below the surface. To survive the harsh winters of their subarctic climates they scrape snow with their hooves to clear areas for browsing on mosses and lichens. Moose are solitary animals and do not form herds, although during the autumn mating season males will battle for females. (1/3)

©Rich Beckman

Moose are the largest members of the deer family, weighing between 800 and 1,500 pounds. In Denali Park, about 2,000 moose roam on the north side of the Alaska Range. Only the males have antlers, which can measure up to six feet from end to end. They prefer to browse on tall grasses and shrubs or in lakes, rivers or wetlands, feeding on aquatic plants at and below the surface. To survive the harsh winters of their subarctic climates they scrape snow with their hooves to clear areas for browsing on mosses and lichens. Moose are solitary animals and do not form herds, although during the autumn mating season males will battle for females. (2/3)

©Rich Beckman

Moose are the largest members of the deer family, weighing between 800 and 1,500 pounds. In Denali Park, about 2,000 moose roam on the north side of the Alaska Range. Only the males have antlers, which can measure up to six feet from end to end. They prefer to browse on tall grasses and shrubs or in lakes, rivers or wetlands, feeding on aquatic plants at and below the surface. To survive the harsh winters of their subarctic climates they scrape snow with their hooves to clear areas for browsing on mosses and lichens. Moose are solitary animals and do not form herds, although during the autumn mating season males will battle for females. (3/3)

©Rich Beckman

Dall Sheep are found in open alpine ridges, meadows, and steep slopes near extremely rugged ground that allows escape from predators (bears, wolves and coyotes) that cannot travel as quickly through such terrain. (1/4)

©Rich Beckman

Dall Sheep are the northernmost wild sheep in the world. Their age can be calculated from the number of growth rings on their horns. They feed on grasses, shrubs and sedges, as well as lichens, willows and mosses when other vegetation is in short supply. During the winter mating (rutting) season, males compete for females, often through violent confrontations slamming the horns together to establish dominance. Dall Sheep are found in open alpine ridges, meadows, and steep slopes near extremely rugged ground that allows escape from predators (bears, wolves and coyotes) that cannot travel as quickly through such terrain. (2/4)

©Rich Beckman

Dall Sheep are the northernmost wild sheep in the world. Their age can be calculated from the number of growth rings on their horns. They feed on grasses, shrubs and sedges, as well as lichens, willows and mosses when other vegetation is in short supply. During the winter mating (rutting) season, males compete for females, often through violent confrontations slamming the horns together to establish dominance. Dall Sheep are found in open alpine ridges, meadows, and steep slopes near extremely rugged ground that allows escape from predators (bears, wolves and coyotes) that cannot travel as quickly through such terrain. (3/4)

©Rich Beckman

Dall Sheep are the northernmost wild sheep in the world. Their age can be calculated from the number of growth rings on their horns. They feed on grasses, shrubs and sedges, as well as lichens, willows and mosses when other vegetation is in short supply. During the winter mating (rutting) season, males compete for females, often through violent confrontations slamming the horns together to establish dominance. Dall Sheep are found in open alpine ridges, meadows, and steep slopes near extremely rugged ground that allows escape from predators (bears, wolves and coyotes) that cannot travel as quickly through such terrain. (4/4)

©Rich Beckman

A rainbow forms as the moon sets over the Alaska Range as seen from Polychrome Overlook at Mile 46 of the Denali Park Road. It is named after the area's multi-colored bluffs high above the glacier fed tributaries of the East Fork of the Toklat River in the tundra region, where a layer of permanently frozen subsoil (permafrost) exists.

©Rich Beckman

Mountain goats are members of the antelope family and live at elevations of 10,000 feet and higher. Goats that live above the timberline during the summer remain there during winter with only short excursions to lower elevations to feed on the tips of trees and other vegetation. In the spring, a nanny goat usually gives birth to a single kid, which will be on its feet within minutes of birth. Mountain goats are herbivores and spend most of their time grazing, eating plants, grasses, mosses and other alpine vegetation. Females, called nannies, spend most of the year in herds with their kids, while males either live alone or with two-three other males.

©Rich Beckman

Only Brown Bear sows without cubs breed, most often in the spring. A dominant boar may mate with several sows a year and sows may breed with more than one male. A pregnant female benefits from the delayed implantation of the blastocyst into the wall of the uterus, allowing her to expend little energy on the developing fetus until the beginning of winter when she goes into hibernation.

Sows give birth while hibernating. When emerging from the den, sows with newborn cubs often stay near the den for one to two weeks while the cubs adapt to their environment. Newborns often have a pale band around their neck referred to as a natal collar. They are often playful and play fighting teaches them to protect themselves. Occasionally, however, there is a need for discipline. (1/2)

©Rich Beckman

Only Brown Bear sows without cubs breed, most often in the spring. A dominant boar may mate with several sows a year and sows may breed with more than one male. A pregnant female benefits from the delayed implantation of the blastocyst into the wall of the uterus, allowing her to expend little energy on the developing fetus until the beginning of winter when she goes into hibernation.

Sows give birth while hibernating. When emerging from the den, sows with newborn cubs often stay near the den for one to two weeks while the cubs adapt to their environment. Newborns often have a pale band around their neck referred to as a natal collar. They are often playful and play fighting teaches them to protect themselves. Occasionally, however, there is a need for discipline. (2/2)

©Rich Beckman

A lone grizzly traverses the scrub brush along the Denali Park Road between the Eielson Visitor Center and Wonder Lake on an autumn afternoon. The road parallels the McKinley River with views of Mt. Mather, Mt. Deception, Mt. Brooks, Mt. Silverthrone and the South Peak of Denali (on a clear day).

©Rich Beckman

In Denali, bears typically den in late October or early November. On average, sows spend up to seven months in hibernation and can lose up to 100 lbs. during that time. Males usually hibernate for five to six months. When they emerge from their dens, the terrain is often snow covered and bears dig for roots, search for winter kills and devour early spring berries and grasses.

©Rich Beckman

The Willow Ptarmigan is the state bird of Alaska. It is an arctic grouse that displays seasonal color changes from a mottled brown or gray in summer to snow white in winter as camouflage from predators. In winter, its feet are heavily feathered which improves its ability to walk through fresh snow. It is herbivorous and forages for buds, twigs, leaves, seeds and berries, although in Alaska it feeds mostly on willows throughout the year.

©Rich Beckman

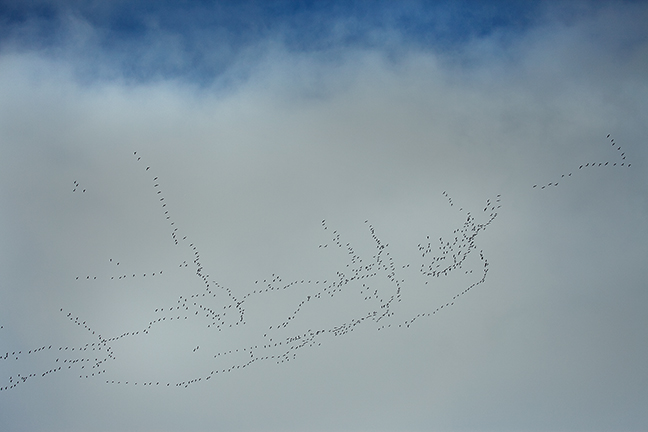

Sandhill Cranes begin their fall migration over the Wonder Lake region of Denali National Park. They are part of the Midcontinent or Central Flyway flock that gather annually and head to their wintering grounds in the Southwest. Their migration corridor is shaped like an hourglass, narrowing over the Platte River basin in Nebraska. During migration and on their wintering grounds, their flocks number in the tens of thousands.

©Rich Beckman

Seasons change quickly in Denali and road closures are common in late August and September due to heavy rains and snow at higher elevations. Each September, after the park officially closes, the park hosts a four-day “road lottery” that allows winners single day personal vehicle access to the park. In 2015, we were able to travel the entire length of the road, after a two-hour snow delay at Toklat River. In September, park visitors often experience both fall and winter along the 90-mile Denali Park Road. (1/4)

©Rich Beckman

Seasons change quickly in Denali and road closures are common in late August and September due to heavy rains and snow at higher elevations. Each September, after the park officially closes, the park hosts a four-day “road lottery” that allows winners single day personal vehicle access to the park. In 2015, we were able to travel the entire length of the road, after a two-hour snow delay at Toklat River. In September, park visitors often experience both fall and winter along the 90-mile Denali Park Road. (2/4)

©Rich Beckman

Seasons change quickly in Denali and road closures are common in late August and September due to heavy rains and snow at higher elevations. Each September, after the park officially closes, the park hosts a four-day “road lottery” that allows winners single day personal vehicle access to the park. In 2015, we were able to travel the entire length of the road, after a two-hour snow delay at Toklat River. In September, park visitors often experience both fall and winter along the 90-mile Denali Park Road. (3/4)

©Rich Beckman

Seasons change quickly in Denali and road closures are common in late August and September due to heavy rains and snow at higher elevations. Each September, after the park officially closes, the park hosts a four-day “road lottery” that allows winners single day personal vehicle access to the park. In 2015, we were able to travel the entire length of the road, after a two-hour snow delay at Toklat River. In September, park visitors often experience both fall and winter along the 90-mile Denali Park Road. (4/4)

©Rich Beckman

It used to be fairly common to see Gray Wolves along the Denali Park Road, as three known packs, Grant Creek, Nenana Canyon and East Fork, denned nearby. However, in spring 2015, Park biologists counted only 49 wolves in the Park, as these packs have been decimated by trapping and hunting on state lands east of the park boundary. The Alaska Board of Game eliminated the no-trapping, no-hunting buffer in 2010 and has turned down repeated emergency petitions requesting reinstatement of a wolf protection zone along the Park’s northeastern edge.

©Rich Beckman