M/S Origo was built 1955 at Finnboda shipyard in Sweden for the Swedish Maritime Administration as an ice-strengthened pilot ship. She now spends her summers as a charter in the Arctic waters of Svalbard.

©Rich Beckman

We traveled with environmental photographer Yves Adams (shown above), based in Belgium, and Swiss Expedition Leader Martin Enckell to Svalbard in July 2015 on the M/S Origo.

©Rich Beckman

In the early 90´s the M/S Origo was refurbished and rebuilt into an expedition ship. She has been in continuous operation in Svalbard, where regulations restrict the number of passengers to 12 persons occupying 12 single or twin cabins, longer than any other ship. In 2016, she will celebrate her 25th year as an expedition ship.

©Rich Beckman

The M/S Origo carries two Zodiacs that allow for cruising around ice floes and along the edge of the ice sheet to view wildlife and to go ashore and visit walrus haulouts and seabird colonies.

©Rich Beckman

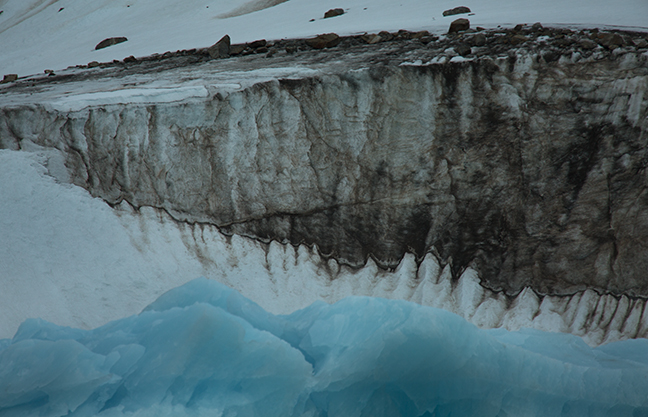

In areas where more snow falls than melts, snow becomes a glacier when the layers begin to deform due to the weight of the overlying snow and ice. Red wavelengths are absorbed by the dense ice and the blue (shorter) wavelengths are transmitted and reflected back to the viewer. Glaciers on Svalbard are retracting and many are already grounded and no longer calving ice into the sea. (1/5)

©Rich Beckman

In areas where more snow falls than melts, snow becomes a glacier when the layers begin to deform due to the weight of the overlying snow and ice. Red wavelengths are absorbed by the dense ice and the blue (shorter) wavelengths are transmitted and reflected back to the viewer. Glaciers on Svalbard are retracting and many are already grounded and no longer calving ice into the sea. (2/5)

©Rich Beckman

In areas where more snow falls than melts, snow becomes a glacier when the layers begin to deform due to the weight of the overlying snow and ice. Red wavelengths are absorbed by the dense ice and the blue (shorter) wavelengths are transmitted and reflected back to the viewer. Glaciers on Svalbard are retracting and many are already grounded and no longer calving ice into the sea. (3/5)

©Rich Beckman

In areas where more snow falls than melts, snow becomes a glacier when the layers begin to deform due to the weight of the overlying snow and ice. Red wavelengths are absorbed by the dense ice and the blue (shorter) wavelengths are transmitted and reflected back to the viewer. Glaciers on Svalbard are retracting and many are already grounded and no longer calving ice into the sea. (4/5)

©Rich Beckman

In areas where more snow falls than melts, snow becomes a glacier when the layers begin to deform due to the weight of the overlying snow and ice. Red wavelengths are absorbed by the dense ice and the blue (shorter) wavelengths are transmitted and reflected back to the viewer. Glaciers on Svalbard are retracting and many are already grounded and no longer calving ice into the sea. (5/5)

©Rich Beckman

Svalbard marks the northernmost limit of the range of the Harbor Seal. Their only known breeding site in the Archipelago is on Prins Karls Forland, an island on the west coast of Spitsbergen. They are found as far south as southern California and the south of France to arctic waters of the North Atlantic and North Pacific Oceans. (1/2)

©Rich Beckman

Svalbard marks the northernmost limit of the range of the Harbor Seal. Their only known breeding site in the Archipelago is on Prins Karls Forland, an island on the west coast of Spitsbergen. They are found as far south as southern California and the south of France to arctic waters of the North Atlantic and North Pacific Oceans. (2/2)

©Rich Beckman

Bearded seals are found year-round at low densities in all of Svalbard’s fjords and in coastal regions wherever there is drifting ice. They prefer drifting pack ice in areas over shallow water shelves. It is unusual to see a bearded seal on land. Except during the breeding season, bearded seals are for the most-part solitary animals. (1/2)

©Rich Beckman

Bearded seals are found year-round at low densities in all of Svalbard’s fjords and in coastal regions wherever there is drifting ice. They prefer drifting pack ice in areas over shallow water shelves. It is unusual to see a bearded seal on land. Except during the breeding season, bearded seals are for the most-part solitary animals. (2/2)

©Rich Beckman

The Blue Whale is the largest animal ever to have lived on Earth. In the Northern Hemisphere they average from 80 to 90 feet in length. Blue Whales were slaughtered to the brink of extinction by commercial whaling and they remain endangered. The global population size is not known, but it is likely around 6,000 animals. The principle diet of blue whales is krill and they tend to seasonally follow the food supply, moving north as temperatures warm.

©Rich Beckman

Icebergs form when chunks of ice calve from glaciers, ice shelves or larger icebergs. Icebergs float because they are lighter than water, although only 10 percent is actually above water. Because glaciers are land-based, icebergs are created from pure, fresh water and snow. North Atlantic icebergs are usually peaked and irregular in shape while Antarctic icebergs are usually tabular, with flat tops and steep sides.

©Rich Beckman

Walruses reside year-round in Svalbard waters. They were hunted for their ivory to virtual extinction during three and a half centuries of commercial exploitation. Walruses became protected 1952. The Svalbard population is thought to include about 2,000 animals. Haul-outs are usually ice pans, although terrestrial haul-out sites are used in the summer and autumn.

©Rich Beckman